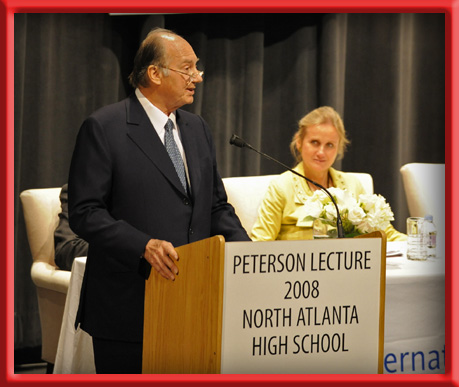

Speech by His Highness the Aga Khan “Global Education and the Developing World”

— The Peterson Lecture addressed to the International Baccalaureate 40th Annual Meeting

Atlanta, Georgia

April 18, 2008

Video of this speech at AKDN: http://www.akdn.org/videos_detail.asp?VideoId=9

Dr. Monique Seefried, Chairman of the IB Board of Governors

Members of the Board of Governors

Mr. Jeffrey Beard, Director General of the IB

Educators and Students from the IB Community

Distinguished Guests

What a great privilege it is for me to be with you today – I have looked forward to this gathering for a long time. And I am particularly grateful to Monique Seefried for her generous introduction, and for so beautifully describing both the local and the global context in which we meet.

This is a particularly significant occasion for me, for several reasons.

It is significant of course because it marks the 40th anniversary of what I regard as one of the great seminal institutions of our era – the International Baccalaureate program. I say that because the IB program incarnates a powerful idea, the confidence that education can reshape the way in which the world thinks about itself.

I am deeply honored to be giving this particular Lecture – the Peterson Lecture, as it, too, has a great legacy. It fittingly celebrates the life and work of Alec Peterson, whose intellectual and moral leadership have been central to this organization and to all whom it has influenced.

I was humbled when I was first invited to be the Peterson Lecturer. That sense of deference grew, I must confess, as I began to look at the distinguished list of former Lecturers. And then I took one more step, and looked at what these people have said through the years – and I was even more deeply impressed by the responsibility of this assignment.

The Peterson Lectures – collected together – would make a wonderful reading list, for an excellent University course, on the topic of international education. After looking through them, I wondered if there was anything left to say on the subject! But if anyone should ever incorporate these lectures into a university syllabus, then perhaps my remarks today could appropriately be placed under the heading of “optional additional reading!”

Finally, this occasion has special meaning for me because it comes, as you may know, on my 50th anniversary as spiritual leader, or Imam, of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. We are thus celebrating both a fortieth and a fiftieth anniversary today – and both provide important opportunities to connect our past with our future, our roots with our dreams.

I came upon a rather striking surprise in looking through the texts of earlier Peterson Lectures. Not just one – but two of those addresses in recent years have quoted my grandfather! It was from him, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, that I inherited my present role in 1957. I also inherited from him a deep concern for the advancement of education – especially in the developing world. These two topics – education and development – have been at the heart of my own work over the past fifty years, and they will form the central theme of my comments today.

Very early after the end of the second world war, my brother and I were sent to school in Switzerland, Le Rosey, and after a few years at that school, a new coach for rowing became part of the school and we were told that he would also coach the ice hockey team during the winter term. His name was Vaclav Rubik, not the one of Rubik’s cube fame but rather, like the famous cube itself, a challenging influence. He was also one of the most talented and intelligent sportsmen that I have ever met. He was in the Czech national ice hockey team which has been one of the best in the world, and he was also in the national Eights and Fours without Coxswain. His wife was in the Czech national field hockey team. So Le Rosey was extremely fortunate to have two exceptional athletes available for coaching. But there was another dimension to Vaclav Rubik. He had a doctorate in Law, and he and his wife were political refugees who had fled on foot all the way from Czechoslovakia to Switzerland. He was a charismatic individual, and after only a couple of years of training he succeeded in putting together an under-18 crew of Fours, which won just about every race it competed in, including the Swiss National Championship for all ages.

We used to spend long hours in buses driving from one rowing competition to another, and from one ice hockey match to another. I remember asking him what he intended to do, as I could not see a man of such quality remaining indefinitely as a sports coach in a small Swiss school. His answer was that he had applied for acceptance as a political refugee to the United States, and that as soon as he would be allowed to come here he would do so. I asked him how he would earn his living once he came to the United States, as I was certain that he would not want to continue his career as a sports coach, and his answer has remained in my mind ever since. He said, my wife and I fled from Czechoslovakia with nothing, other than the clothes on our back and the shoes on our feet, but I have had a good education and when I arrive in the United States, that is what will enable me to obtain the type of employment I would wish. Once he left Le Rosey, I somewhat lost touch with him, and the last thing I heard was that he had become a very senior executive in the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

The moral of the story is clear – you can have nothing in your pocket, and only the clothes and the shoes you wear, but if you have a well educated mind, you will be able to seize the opportunities life offers you, and start all over again.

I suspect that many members of the Ismaili Community, like other Asians who were expelled by Idi Amin from Uganda, and who made successful new lives in other parts of the world, would tell you the same story.

From its very beginnings, the International Baccalaureate Organization has understood this central truth. But as we move into a new century, I would like to combine my words of congratulation and commendation, with some words of inquiry and challenge.

What is the eventual place and purpose of the IB in developing societies – and in a Muslim context? What can those worlds contribute to the IB community? And how can institutions which are rooted in different cultural traditions best work together to bridge worlds that have too often been widely separated?

As a point of departure in addressing these questions, I would turn to those words from my Grandfather which were quoted in two earlier Peterson Lectures. He included them in a speech he gave as President of the League of Nations in Geneva some 70 years ago. They come originally from the Persian poet, Sadi, who wrote:

“The children of Adam, created of the self-same clay, are members of one body. When one member suffers, all members suffer, likewise. O Thou, who art indifferent to the suffering of the fellow, thou art unworthy to be called a man.”

You will readily understand why such words seem appropriate for a Peterson Lecture. They speak to the fundamental value of a universal human bond- a gift of the Creator – which both requires and validates our efforts to educate for global citizenship.

I would also like to quote an infinitely more powerful statement about the unity of mankind, because it comes directly from the Holy Quran, and which I would ask you to think about. The Holy Quran addresses itself not only to Muslims, but to the entirety of the human race, when it says:

“O mankind! Be careful of your duty to your Lord Who created you from one single soul and from it created its mate and from them twain hath spread abroad a multitude of men and women.”

These words reflect a deeply spiritual insight – A Divine imperative if you will – which, in my view, should under gird our educational commitments. It is because we see humankind, despite our differences, as children of God and born from one soul, that we insist on reaching beyond traditional boundaries as we deliberate, communicate, and educate internationally. The IB mission statement puts it extremely well: “to encourage students across the world to become active, compassionate and lifelong learners who understand that other people, with their differences, can also be right.”

The IB community has thought long and hard about what it means for students to become powerfully aware of a wider world – and to deal effectively with both its bewildering diversity and its increasing interdependence. The IB program has wrestled vigorously with one of the basic conundrums of the age – how to take account of two quite different challenges.

The first challenge is the fact that the world is increasingly a “single” place – a wondrous web of global interaction cutting across the lines of division and separation which have characterized most of its history. This accelerating wave of interdependence is something we first defined as “internationalization” when the IB program was launched 40 years ago. We refer to it now as “globalization.” It brings with it both myriad blessings and serious risks – not the least of which is the danger that globalization will become synonymous with homogenization.

Why would homogenization be such a danger? Because diversity and variety constitute one of the most beautiful gifts of the Creator, and because a deep commitment to our own particularity is part of what it means to be human. Yes, we need to establish connecting bonds across cultures, but each culture must also honour a special sense of self.

The downside of globalization is the threat it can present to cultural identities.

But there is also a second great challenge which is intensifying in our world. In some ways it is the exact opposite of the globalizing impulse. I refer to a growing tendency toward fragmentation and confrontation among peoples. In a time of mounting insecurity, cultural pride can turn, too often, into an endeavour to normatise one’s culture. The quest for identity can then become an exclusionary process – so that we define ourselves less by what we are FOR and more by whom we are AGAINST. When this happens, diversity turns quickly from a source of beauty to a cause of discord.

I believe that the coexistence of these two surging impulses – what one might call a new globalism on one hand and a new tribalism on the other – will be a central challenge for educational leaders in the years ahead. And this will be particularly true in the developing world with its kaleidoscope of different identities.

As you may know, the developing world has been at the centre of my thinking and my work throughout my lifetime. And I inherited a tradition of educational commitment from my grandfather. It was a century ago that he began to build a network of some 300 schools in the developing world the Aga Khan Education Services – in addition to founding Aligarh University in India.

The legacy which I am describing actually goes back more than a thousand years, to the time when our forefathers, the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs of Egypt, founded Al-Azhar University and the Academy of Knowledge in Cairo. For many centuries, a commitment to learning was a central element in far-flung Islamic cultures. That commitment has continued in my own Imamat through the founding of the Aga Khan University and the University of Central Asia and through the recent establishment of a new Aga Khan Academies Program.

And this is where your and our paths meet.

As you have heard, the curriculum of our Academies is centered on the IB program. We hope that the network of Aga Khan Academies will become an effective bridge for extending the IB Program more widely into the developing world.

Each of you knows well the IB side of this bridge. I thought I might add just a few words about the Academies side of the bridge, and about my purpose in initiating this international network of high quality schools.

Our Academies Program is rooted in the conviction that effective indigenous leadership will be the key to progress in the developing world, and as the pace of change accelerates, it is clear that the human mind and heart will be the central factors in determining social wealth.

Yet in too much of the developing world, the capacity to realise the potential of the human resource base is still sadly limited. Too many of those who should be the leaders of tomorrow are being left behind today. And even those students who do manage to get a good education often pursue their dreams in far off places – and never go home again. The result is a widening gap between the leadership these communities need – and the leadership their educational systems deliver.

For much of human history, leaders have been born into their roles, or have fought their way in – or have bought their way in. But in this new century – a time of unusual danger and stirring promise, it is imperative that aristocracies of class give way to aristocracies of talent – or to use an even better term – to meritocracies. Is it not a fundamental concept of democracy itself, that leadership should be chosen on the basis of merit?

Educating for leadership must imply something more than the mere developmennt of rote skills. Being proficient at rote skills is not the same thing as being educated. And training that develops skills, important as they may be, is a different thing from schooling in the art and the science of thinking.

The temptation to inculcate rather than to educate is understandably strong among long frustrated populations. In many such places, public emotions fluctuate between bitter impatience and indifferent skepticism – and neither impatience nor indifference are favorable atmospheres for encouraging reasoned thought.

But in an age of accelerating change, when even the most sophisticated skills are quickly outdated, we will find many allies in the developing world who are coming to understand that the most important skill anyone can learn is the ability to go on learning.

In a world of rapid change, an agile and adaptable mind, a pragmatic and cooperative temperament, a strong ethical orientation – these are increasingly the keys to effective leadership. And I would add to this list a capacity for intellectual humility which keeps one’s mind constantly open to a variety of viewpoints and which welcomes pluralistic exchange.

These capacities, over the longer term, will be critically important to the developing world. They happen to be the same capacities which programs like the IB – and the Aga Khan Academies – are designed to elicit and inspire.

The Academies have a dual mission: to provide an outstanding education to exceptional students from diverse backgrounds, and to provide world-class training for a growing corps of inspiring teachers.

At these 18 Academies, each educating between 750 to 1200 primary and secondary students, we anticipate having one teacher for every seven students, and we will place enormous emphasis on recruiting, training, and compensating them well. We hope they will become effective role models for other teachers in their regions.

To this end, we expect within the next year or so to open new Professional Development Centres for teacher education in India, Bangladesh, Mozambique, and Madagascar. Similar planning is underway in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Tanzania and Uganda. These Professional Development Centres will operate before we open the doors to students.

In sum, our strategy begins with good teaching. We must first teach the teachers.

As the Academies open, one-by-one, they will feature merit-based entry, residential campuses, and dual-language instruction. This language policy exemplifies our desire to square the particular with the global. English will enable graduates to participate fully on an international stage, while mother-tongue instruction will allow students to access the wisdom of their own cultures.

Squaring the particular with the global will require great care, wisdom, and even some practical field testing, to ensure that it really is possible to develop a curriculum that responds effectively to both the global and the tribal impulses. While this will be a feat in itself, it will also be important to relate well to highly practical concerns such as the nature of each country’s national university entrance exams, and the the human resources required by each country’s multi-year development plans.

The Academies have given much thought to the components that we would describe as global in our curriculum. We intend to place special emphasis on the value of pluralism, the ethical dimensions of life, global economics, a broad study of world cultures (including Muslim Civilizations) and comparative political systems. Experienced IB teachers have already been helping us to integrate these important areas of focus into the Academies curriculum.

Many students will also study for at least a year in other parts of the Academy network, outside their home countries. And of course we have stipulated that our program should qualify our students for the International Baccalaureate diploma. Faculty too will have the opportunity to live in new countries, learn new languages and engage in new cultures.

You may be asking yourselves on what bases the Aga Khan Education Services and the Academies Program have selected new subjects to be added to the Academies curriculum, and I thought it might be useful to illustrate that to you.

With regard to pluralism, it has been our experience that in a very large number of countries in Europe, in Asia, in Africa, in the Middle East, and elsewhere, the failure of different peoples to be able to live in peace amongst each other has been a major source of conflict. Experience tells us that people are not born with the innate ability nor the wish to see the Other as an equal individual in society. Pride in one’s separate identity can be so strong that it obscures the instrinsic value of other identities. Pluralism is a value that must be taught.

With regard to the issue of ethics, we see competent civil society as a major contributor to development, particularly where democracies are weak, or where governments have become dysfunctional. We are therefore concerned with the quality of ethics in all components of civil society, and reject the notion that the absence of corruption or fraud in government is anywhere near sufficient, to ensure to every individual a rigorous and clean enabling environment. Fraud in medicine, fraud in education, fraud in financial services, fraud in property rights, fraud in the exercise of law enforcement or in the courts, are risks which have a dramatic effect on peoples’ development. This is especially true in rural environments where the majority of the peoples of the developing world live, but where fraud is often neither reported nor corrected, but simply accepted as an inevitable condition of life.

Educating for global economics will also be essential to ensure that the failed economic systems of the past are replaced. But this must not mean a simplistic acceptance of the imbalances and inequities associated with today’s new global economy. We need to develop a broad consensus which focuses on creating a global economic environment which is universally fair.

Our program will also teach about world cultures. Inter-cultural conflicts inevitably grow out of intercultural ignorance – and in combating ignorance we also reduce the risk of conflict.

Finally, we want to educate about comparative political systems, so that more and more people in the developing world will be able to make competent value judgements about their Constitutions, their political systems, and how they can best develop democratic approaches which are well tailored to their needs. Public referenda, to sanction new Constitutions, for example, make little sense when they call for judgments from people who do not understand the questions they are being asked, nor the alternatives they should be considering.

These planned subject areas share two characteristics: They all impact a large number of countries across the continents of our world, and they address problems that will take many decades to resolve. And, while the Academies have made reasonable progress in defining the broad areas of the curriculum, I must be frank in saying that the more tribal subjects, specific to individual countries, or perhaps regions, are areas where a great deal of work remains to be done, and where in fact we should expect to go through a prudent step-by-step process – cutting the cloth as each individual situation requires.

What we hope to create, in sum, is a network of 18 educational laboratories, all of them sharing a common overriding purpose, but each one learning from the others particular experiences.

The first Aga Khan Academy opened in Kenya four years ago, and the first cohort of IB Diploma graduates completed their studies last June. The quality of their academic work, including their success on the IB examinations, along with their records of community service, make us optimistic about the future.

As we move into that future, we would like to collaborate with the International Baccalaureate movement in a challenging, but inspiring new educational adventure. Together, we can help reshape the very definition of a well educated global citizen. And we can begin that process by bridging the learning gap which lies at the heart of what some have called a Clash of Civilizations, but which I have always felt was rather a Clash of Ignorances.

In the years ahead, should we not expect a student at an IB school in Atlanta to know as much about Jomo Kenyatta or Muhammad Ali Jinnah as a student in Mombasa or Lahore knows about Atlanta’s great son, the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr.? Should a Bangladeshi IB student reading the poems of Tagore at the Aga Khan Academy in Dhaka not also encounter the works of other Nobel Laureates in Literature such as the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk or America’s William Faulkner or Toni Morrison?

Should the study of medieval architecture not include both the Chartres Cathedral in France and the Mosque of Djenne in Mali? And shouldn’t IB science students not learn about Ibn al-Haytham, the Muslim scholar who developed modern optics, as well as his predecessors Euclid and Ptolemy, whose ideas he challenged.

As we work together to bridge the gulf between East and West, between North and South, between developing and developed economies, between urban and rural settings, we will be redefining what it means to be well educated.

Balancing the universal and the particular is an age old challenge – intellectually and practically. But it may well become an even more difficult challenge as time moves on and the planet continues to shrink. It is one thing, after all, to talk about cultural understanding when “the Other” is living across the world. It is often a different matter when the “Other” is living across the street.

I admire the IB organization’s desire to take on the cultural challenges of our time, to move into parts of the world and areas of society where it has been less active in the past. But we all should be clear, as we embark on such projects, that the people with whom we will be dealing will present different challenges than before. As we choose our targets of opportunity, we should examine the environments and consider carefully the changes which can make these programs most relevant to the future.

Some people tell us that globalization is an inevitable process. That may be true in certain areas of activity – but there is nothing inevitable about globalizing educational approaches and standards. Conceptualising a global examination system is one of the most difficult intellectual endeavours I can imagine – though it should also be one of the most exciting. The intellectual stimulation of working on such a project could keep the world’s best educators engaged for decades. That task may be more feasible, however, because of the head start which the IB organization has already made in thinking about a global curriculum. Your IB experience, independent of the Aga Khan Academies, as well as your Peterson lectures through the years offer an excellent foundation for that process.

As the IB moves beyond the Judeo-Christian cultures where it is most experienced, it will have to make educators in other areas of the world into its newest stakeholders. This will probably mean developing more explicit expressions of a cosmopolitan ethic, founded if possible in universal human values. That may well be a progressive, ever evolving process – one that will be increasingly inclusive but may never be complete.

What would it mean for example for the IB program to work in largely rural societies -where there have never been the resources or incentives to support serious and sustained education? What would it mean to apply the concepts of critical thinking and individual judgment in societies which are steeped in habitual deference to age and authority, to rules and to rituals.

What would it require for an organization which is deeply rooted in the Western humanist tradition to speak with relevance in profoundly non-Western cultural settings? And how should we go about the challenges of moral education – growing out of universal values -in settings where religious and ideological loyalties are particularly intense.

I ask these questions not because I have ready answers to them – but because I think the posing of such questions will be essential to our progress. I ask them not to discourage you from reaching out – but rather to encourage you – as you do reach out – to do so with a full understanding of the risks and the strains that you will inevitably encounter.

I believe we can find answers to these questions. They may not be full and complete and perfect answers, but there at least will be initial answers, tentative answers, working answers. And each step along the way will teach us more.

What is essential is that we search.

In the final analysis, the great problem of humankind in a global age will be to balance and reconcile the two impulses of which I have spoken: the quest for distinctive identity and the search for global coherence.What this challenge will ultimately require of us, is a deep sense of personal and intellectual humility, an understanding that diversity itself is a gift of the Divine, and that embracing diversity is a way to learn and to grow – not to dilute our identities but to enrich our self-knowledge.

What is required goes beyond mere tolerance or sympathy or sensitivity – emotions which can often be willed into existence by a generous soul. True cultural sensitivity is something far more rigorous, and even more intellectual than that. It implies a readiness to study and to learn across cultural barriers, an ability to see others as they see themselves. This is a challenging task, but if we do that, then we will discover that the universal and the particular can indeed be reconciled. As the Quran states: “God created male and female and made you into communities and tribes, so that you may know one another.” (49.13) It is our differences that both define us and connect us.

I am confident that the IB program will continue to succeed as it extends its leadership into new arenas in the decades ahead. But as that happens, one key variable will be the spirit in which we approach these new engagements.

There will be a strong temptation for us to regard these new frontiers as places to which we can bring some special gift of accumulated knowledge and well seasoned wisdom. But I would caution against such an emphasis. The most important reason for us to embrace these new opportunities lies not so much in what we can bring to them as in what we can learn from them.

Thank you very much.

18 April 2008

Your Highness the Aga Khan;

Members of the Consular Corps;

representatives of the Ismaili community and the government of Georgia;

representatives of universities and IB World Schools worldwide;

attendees of the Global Language Convention viewing this Lecture via simulcast;

teachers and students of North Atlanta High School, the hosts of this special meeting,

members of IB Georgia Schools Association,

IB Board and staff members,

ladies and gentlemen,

friends and colleagues,

my warmest welcome to this 2008 Peterson Lecture.

The fact that this year’s Peterson Lecture is being held in Atlanta, and in an IB World School at that, is of special significance, both to me personally and to the IB.

My adopted city of Atlanta, as many of you know, is where my children were raised and educated, where I have for many years been engaged with Emory University and the Carlos Museum, the Atlanta International School, and where I founded the Center for the Advancement and Study of International Education (CASIE) here to promote multi-language programmes and international understanding in K-12 schools in the United States. Over the years I have been witness to the growth of the IB in Atlanta and Georgia as more and more students of different ages and backgrounds have gained access to the quality and values of IB programmes. For those of you who are unfamiliar with the nearby schools, I invite you to visit the exhibition of student work later on during the reception, and talk to some of the students who have come along.

In previous years of course we have held the Peterson Lecture in some historic locations; including the Château de Coppet and the International Conference Centre in Geneva; but hosting it on this occasion in an IB World School, and an IB World School in Atlanta, is a valuable reminder of what the IB is really all about: IB students and the impact that they are making, the impact they will make, on the world around them.

Looking at the banners and publications around you, you will have realized that this year, 2008, is also the 40th anniversary of the creation of the IB Diploma Programme. We are honoured to have here with us today various pioneers and contributors to the IB, in the early years when it started out as the “diploma project” and was taught in a handful of schools, and then growing and expanding through the years to a point where we have three programmes covering K-12 being taught to over half a million students in over 2,300 schools in 126 countries around the world; I offer a special word of welcome to the former director general Roger Peel and president of the Council of Foundation Greg Crafter here present, as well as former members of governance, management and heads of schools who have travelled considerable distances to be here with us and celebrate this important event. I also would like to give a very special thank you to North Atlanta High School, its staff as well as its IB and ROTC students for hosting us here today as well as the IB Georgia Association, and the 40 schools that have turned this event into a real celebration and have prepared an exhibition for us all to see what an IB education can inspire them to do.

Since this is the fortieth anniversary of the IB, and we are in Atlanta, let us travel back to the city in 1968. The United States, the world, is witnessing the turmoil of friction and unrest while looking to an uncertain future. Atlanta is a segregated city in a segregated country. Most entrenched of all is the segregation of education – the unjust law that kept young people separate from one another in schools. And along comes Atlanta-born Martin Luther King, Jr., the harbinger of hope for millions of Americans. 1968 is the year he is assassinated, but not before he changes the face of the world. Martin Luther King’s philosophy of non-violence was partly influenced by the work of Mahatma Gandhi; and he was also interested in Gandhi’s theories about the need for education to be based on the fundamental assumption of the goodness of human beings and an awareness of the impact of all actions on oneself, society and nature. Martin Luther King showed a lifelong love of learning through formal education, entering Morehouse College at the young age of fifteen and culminating in his doctoral studies at Boston University where he became a Doctor of Philosophy. Education was so important in Dr. King’s life.

1968 is the year that the IB is founded; by a small group of resolute, forward-looking men and women searching for international peace, searching for the means to educate young people to become the next harbingers of hope. Men and women who had lived through the world wars and knew that children were the only hope. People of vision.

Thanks to their vision we can offer young people today the gift of a high quality IB education; an education that derives its quality from its values as well as from its high standards, high standards that can be reached by anyone who is motivated. We all know that motivation may be intrinsic, but so often it comes from motivated teachers, teachers who love what they teach, care so much for their students that they are able to transmit to them the love for what they teach, the love for learning. The IB teachers are at the core of the IB success, they are the ones instilling in our students the knowledge and the values that will allow them to be builders in the world of tomorrow and to transmit the message of peace and understanding that is so paramount in an IB education.

One of the mechanisms available to them and their students is the IB community theme of “sharing our humanity”. Not only do students in IB World Schools learn from one another in their classrooms – as an example of school practice – but also from fellow students located in any of 126 countries around the world through the IB community theme website; learning about topics such as global poverty, peace and conflict and the digital divide.

Among those IB students, we already have and will have soon many more motivated students from a network of Aga Khan Academies, world-class schools spread across part of the developing world. These day and boarding schools, 18 are in the pipeline right now, are welcoming students of all backgrounds and faiths, regardless of their financial abilities in South and Central Asia, Africa and the Middle East. At the head of this remarkable initiative is His Highness the Aga Khan, our esteemed Peterson Lecture speaker today.

An IB education is an extraordinary gift, and I should not be the one speaking about what it means. Only IB students can describe it. You will see for yourself at the end of this lecture in meeting IB students and seeing their work during the reception that follows this lecture, and I have asked an IB graduate, Karim Thomas, before I introduce His Highness to you, to tell you what the IB has meant to him. He can speak about the IB from personal experience: Karim, would you mind coming to the podium?

I feel so extremely honoured to welcome His Highness to speak at this 2008 Peterson Lecture, during a visit to the USA that commemorates His Golden Jubilee Year. To have him find the time to speak to us today speaks so highly about his commitment to education and his respect for the IB. Before he comes to the podium, allow me to introduce Him to you.

His Highness the Aga Khan became Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims on July 11, 1957 at the age of 20, succeeding his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan. He is the 49th hereditary Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims and a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad (God’s peace be his) through his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, the first Imam, and his wife Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter. The Aga Khan was born on December 13, 1936, in Geneva and spent his early childhood in Nairobi, Kenya, and then attended for nine years Le Rosey School in Switzerland. Le Rosey is now an IB school and its headmaster, Michael Robert Gray, is with us via simulcast from the Global Language Conference where he just finished, very appropriately, presenting a session entitled: Boarding School Babel: A Model for a Multilingual International Learning Environment. After studying at le Rosey, His Highness graduated from Harvard University in 1959 with a BA Honors Degree in Islamic history.

Like his grandfather Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan before him, the Aga Khan has, since assuming the office of Imamat in 1957, been concerned about the well-being of all Muslims, particularly in the face of the challenges of rapid historical changes. Today, the Ismailis live in some 25 countries, mainly in South and Central Asia, Africa and the Middle East, as well as in North America and Western Europe. Over the four decades since the present Aga Khan became Imam, there have been major political and economic changes in most of these areas. He has adapted the complex system of administering the Ismaili Community, pioneered by his grandfather during the colonial era, to a new world of nation-states, which has grown in size and complexity following the independence of the Central Asian Republics of the former Soviet Union.

The Aga Khan has emphasized the view of Islam as a thinking, spiritual faith: one that teaches compassion and tolerance and that upholds the dignity of man, God’s noblest creation. In the Shia tradition of Islam, it is the mandate of the Imam to safeguard the individual’s right to personal intellectual search and to give practical expression to the ethical vision of society that the Islamic message inspires. In following the wisdom of God’s final Prophet in seeking new solutions for problems, which could not be solved by traditional methods, Muslims should be guided to conceive a truly modern and dynamic society, without affecting the fundamental concepts of Islam.

It is for me not only as chairman of the IB board but also personally an incredible honour to be able to introduce His Highness to you. As some of you may know, I was born in Carthage and as a child I spent many summers in Tunisia in the care of the Ben Romdane family. Dr Ben Romdane called me his third daughter, I thought of him as my adoptive father. He took me often to visit the city of his birth, Madhia, the first capital of the Fatimid dynasty, from where the ancestors of the Aga Khan started to rule over the Maghreb, Egypt and part of the Middle East for several centuries. It is in Egypt that they founded the oldest university in the world, the university of Al Azhar. There, the Muslim world preserved the acquisitions of the Greek and Roman world and gave it back to the West that had lost much of it during the Dark Ages following the Barbarian invasions. Growing up, I also recall learning about the accomplishments of the Ismaili community in many charitable hospitals and schools in Eastern Africa under the leadership of His Highness’ grandfather, who, years before, as President of the League of Nations had an early connection with the International School of Geneva and the ideals that gave birth to the International Baccalaureate. Much later, during my professional life as a university professor and museum curator, I witnessed and admired the remarkable work the present Aga Khan instigated in architecture conservation and in the study and conservation of Islamic art through generous grants.

Now as chairman of the IB Board of Governors, I am in the fortunate position of being able to support an important initiative to widen access to IB programmes among students in developing countries who might not normally have the possibility of attending an IB World School. This is happening thanks to the personal commitment of his Highness the Aga Khan.

Driven by the conviction that home-grown intellectual leadership of exceptional calibre is the best driver of society’s future development, and that many developing-country education systems are too engulfed by poverty and numbers to develop their talented young people, He has founded the Aga Khan Academies, the first of which opened in Mombasa, Kenya, in 2003; all Academies are to be located in countries in Africa, South and Central Asia, and the Middle East and as I told you before, they are open to all youngsters who care to apply themselves, regardless of their religious or financial background. The Aga Khan Academies will be an integrated network of residential schools offering girls and boys an international standard of education from pre-primary to secondary levels with a rigorous academic and leadership-development experience. The Aga Khan Academies education is built on the framework of our IB programmes which align with the values of the Aga Khan Development Network in that they are intended to foster an ethical and public-minded approach and give emphasis to the concepts of meritocracy, pluralism, and civil society. This collaboration between the Aga Khan Academies and the IB will benefit both organizations and therefore all IB students. While we celebrate our 40th anniversary, it is very important for the IB to encompass all cultures and to be proud of its international name. While we strive to instil our programs with international mindedness and literacy, we are still seen as a very Western education system. I am so happy that at a stage when the IB reaches its full maturity, it is working together with the Aga Khan Academies, and will benefit from the education resources of the Universities, case studies in development and the cultural assets of the Aga Khan Development Network, allowing it to embrace a global and pluralistic humanism that can only contribute to a stronger influence of our ideals the world over.

Through this partnership with the Aga Khan Development Network we can see clearly the potential for this work to carry on the work of our founders and work in partnership to build a better future. As we build on the work of those who had vision, we, in turn, hope that our vision, our work will lead to the understanding that, “other people, with their differences, can be right”.

Thank you.

Original link: http://www.amaana.org/speeches/ibspeech08.htm

Video of this speech: http://www.akdn.org/videos_detail.asp?VideoId=9

Video Link on C-SPAN http://www.c-span.org/video/?c1963057/clip-tolerance-global-citizenship