by Daftary, Farhad

Source: Institute of Ismaili Studies

Daftary, F. "The Ismaili da'wa Outside the Fatimid dawla," in L'Egypte Fatimide: Son Art et Son Histoire, Marianne Barrucand (ed.) pp. 29 - 43. Paris: Presses de l'Universite de Paris-Sorbonne

Abstract

This article examines the history, structure and successes of the da'wa system prior to and during the establishment of the Fatimid caliphate. Early Ismaili da'wa took advantage of the fact that there were many discontented factions among the Abbasid populace. Acquiring the allegiance of these groups facilitated the eventual establishment of the Fatimid caliphate.

During the reign of the Fatimids, the da'wa structure continued to be refined and expanded. Within the Fatimid state, the da'wa enjoyed unbridled freedom to propagate the faith and expound upon ideological developments. However, the Fatimids' policies of tolerance and freedom of religion prevented Ismailism from ever rooting deeply into the North African population. It remained the faith of a minority for the duration of the Fatimid reign.

Ironically, outside the Fatimid dawla, the da'wa was more successful in establishing significant Ismaili communities across Asia and into the Subcontinent. It is this stability, achieved outside Fatimid territory, which allowed Ismailism's survival and continuation after the decline of the Fatimid dynastic rule.

Keywords

da'i, da'wa, Fatimid, Imamate, Ismailis, Shi‘a, Abbasids, Mustali, Nizari, Hafizi, Tayyibi, Al-Kirmani, Al-Sijistani, Al-Nu'man, Al-Shirazi, Hasan Sabbah, Nasir Khusraw

Table of contents

Background

Aim

of the da'wa system

Ismaili Doctrine

Establishment

of an Ismaili State

Inauguration

of the Fatimid caliphate

Laying

Ideological Foundations

Consolidating

Authority

Continuation

of the da'wa and Codification of Ismaili Law

Key

Tenets of Ismaili Law

Religious Propoganda

[sic] Within and Against the Fatimid dawla

Results

of da'wa Strategies

The Egyptian

Expedition

The

caliph Moves to Egypt

Secrecy

Surrounding da'wa Functioning

Central

da'wa Objectives

da'wa

Methodology

Functions

of the da'i

Majalis

and the Proliferation of Ismaili Ideology

Organisation

of the da'wa

Further

Evolution of the da'wa Organisation

da'wa

Within and Without the dawla

Al-Kirmani's

Success and Abbasid Reactions

da'wa

Expansion in Iraq and Persia

Nasir Khusraw

Philosophical

Ismailism

Success

in Yaman

Fatimid

Decline and Dissension

The

Nizaris Split from Fatimid Headquarters

Fatimid

Disintegration

Further

Offshoots

Ismaili

Survival Amidst Fatimid Collapse

Notes

The Ismailis separated from the rest

of the Imami Shi'is on the death of the Imam

Ja'far al-Sadiq in 148/765. By the middle of the third/ninth century,

the Ismailis had organised a secret, religio-political movement designated

as al-da'wa (the mission) or, more precisely, al-da'wa al-hadiya (the rightly

guiding mission). The over-all aim of this dynamic and centrally-directed

movement of social protest was to uproot the Abbasids and install the `Alid

Imam acknowledged by the Ismailis to the actual rule of the Islamic community

(umma). The revolutionary message of the Ismaili da'wa was systematically

propagated by a network of da'is or religio-political missionaries in different

parts of the Muslim world, from Transoxania to Yaman and North Africa.

Aim of the da'wa System

The Ismaili da'is summoned the Muslims everywhere to accord their allegiance to the Ismaili Imam-Mahdi, who was expected to deliver the believers from the oppressive rule of the Abbasids and establish justice and a more equitable social order in the world. Thus, the Ismaili da'wa also promised to restore the leadership of the Muslims to 'Alids, members of the Ahl al-bayt or the Prophet Muhammad's family, whose legitimate rights to leadership had been successively usurped by the Umayyads and the Abbasids.1 The Ismaili da'is won an increasing number of converts among a multitude of discontented groups of diverse social backgrounds. Among such groups mention may be made of the landless peasantry and Bedouin tribesmen whose interests were set apart from those of the prospering urban classes. The da'is also capitalised on regional grievances. On the basis of a well-designed da'wa strategy, the da'is were initially more successful in non-urban milieus, removed from the administrative centres of the `Abbasid caliphate. This explains the early spread of Ismailism among rural inhabitants and bedouin tribesmen of the Arab lands, notably in southern Iraq, eastern Arabia (Bahrayn) and Yaman. In contrast, in the Iranian lands, especially in the Jibal, Khurasan and Transoxania, the da'wa was primarily addressed to the ruling classes and the educated elite.

The early Ismaili da'wa achieved particular success among those Imami Shi'is of Iraq, Persia and elsewhere, later designated as Ithna'ashariyya (Twelvers), who had been left in a state of disarray and confusion following the death of their eleventh Imam and the simultaneous disappearance of his infant son Muhammad in 260/874. These Imamis shared the same early theological heritage with the Ismailis, especially the Imami doctrine of the Imamate. This doctrine, which provided the central teaching of the Twelver and Ismaili Shi`is, was based on the belief in the permanent need of mankind for a divinely guided, sinless and infallible (ma'sum) Imam who, after the Prophet Muhammad, would act as the authoritative teacher and guide of men in all their spiritual affairs. This Imam was entitled to temporal leadership as much as to religious authority; his mandate, however, did not depend on his actual rule. The doctrine further taught that the Prophet himself had designated his cousin and son-in-law Ali b. Abi Talib (d. 40/661), who was married to the Prophet's daughter Fatima, as his successor under divine command; and that the Imamate was to be transmitted from father to son among the descendants of 'Ali and Fatima, through their son al-Husayn (d. 61/680) until the end of time. This `Alid Imam was in possession of a special knowledge or 'ilm, and had perfect understanding of the exoteric (zahir) and esoteric (batin) meanings of the Qur'an and the commandments and prohibitions of the shari'a or the sacred law of Islam. Recognition of this Imam, the sole legitimate Imam at any time, and obedience to him were made the absolute duties of every believer.2

By 286/899, when the Ismailis themselves split into the loyal Fatimid Ismaili and the dissident Qarmati factions, significant Ismaili communities had appeared in numerous regions of the Arab world and throughout the Iranian lands, as well as in North Africa where the Kutama and other Berber tribal confederations had responded to the summons of the Ismaili da'wa. The dissident Qarmatis did not acknowledge the Imamate of `Abd Allah al-Mahdi (the future founder of the Fatimid caliphate) and his predecessors, the central leaders of early Ismailism, as well as his successors in the Fatimid dynasty. In the same eventful year 286/899, the Qarmatis founded a powerful state of their own in Bahrayn, which survived in rivalry with the Fatimid state until 470/1077.3

Establishment of an Ismaili State

The success of the early Ismaili da'wa was crowned in 297/909 by the establishment of the Fatimid state or dawla in North Africa, in Ifriqiya (today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria). The foundation of this Fatimid Ismaili Shi'i caliphate represented not only a great success for the Ismailiyya, who now possessed for the first time a state under the leadership of their Imam, but for the entire Shi'a. Not since the time of 'Ali, had the Shi'a witnessed the succession of an `Alid to the actual leadership of an important Islamic state. By acquiring political power, and then transforming the nascent Fatimid dawla into a flourishing empire, the Ismaili Imam presented his Shi'i challenge to `Abbasid hegemony and Sunni interpretations of Islam. Ismailism, too, had now found its own place among the state-sponsored communities of interpretation in Islam. Henceforth, the Fatimid caliph-Imam could claim to act as the spiritual spokesman of Shi'i Islam in general, much like the `Abbasid caliph was the mouthpiece of Sunni Islam.

Inauguration of the Fatimid caliphate

On 20 Rabi` II 297/ 4 January 910, the Ismaili Imam `Abd Allah al-Mahdi made his triumphant entry into Raqqada, the Aghlabid capital in Ifriqiya, where he was acclaimed as caliph by the Kutama Berbers and the notables of the uprooted Aghlabid state. On the following day, the khutba was pronounced for the first time in all the mosques of Qayrawan in the name of `Abd Allah al-Mahdi. At the same time, a manifesto was read from the pulpits announcing that leadership had finally come to be vested in the Ahl al-bayt. As one of the first acts of the new regime, the jurists of Ifriqiya were instructed to give their legal opinions in accordance with the Shi'i principles of jurisprudence. The new caliphate and dynasty came to be known as Fatimid (Fatimiyya), derived from the name of the Prophet's daughter Fatima, to whom al-Mahdi and his successors traced their ancestry.

Laying Ideological Foundations

The ground for the establishment of the Fatimid caliphate in Ifriqiya had been carefully prepared since 280/893 by the da'i Abu `Abd Allah al-Shi'i, who had been active among the Kutama Berbers of the Lesser Kabylia. It was from his base in the Maghrib that the da'i al-Shi`i converted the bulk of the Kutama Berbers; and with the help of his Kutama armies he eventually seized all of Ifriqiya. It is to be noted, however, that Shi`ism had never taken deep roots in North Africa, where the native Berbers generally adhered to diverse schools of Kharijism while Qayrawan, founded as a garrison town and inhabited by Arab warriors, remained the stronghold of Maliki Sunnism. Under such circumstances, the newly converted Berbers' understanding of Ismailism, which at the time still lacked a distinctive school of law (madhhab), was rather superficial - a phenomenon that remained essentially unchanged in subsequent decades. The da'i al-Shi'i personally taught the Kutama initiates Ismaili tenets in regular lectures. These lectures were known as the "sessions of wisdom" (majalis al-hikma), as esoteric Ismaili doctrine was referred to as ''wisdom" or hikma. Abu `Abd Allah al-Shi'i instructed his subordinate da'is to hold similar sessions in the areas under their jurisdiction.4 Later, the da`i al-Shi'i's brother Abu'l-`Abbas, another learned da'i of high intellectual calibre, held public disputations with the leading 'Maliki jurists of Qayrawan, expounding the Shi`i foundations of the new regime and the legitimate rights of the Ahl al-bayt to the leadership of the Islamic community. The ground was thus rapidly laid also doctrinally for the establishment of the new Shi`i caliphate.

The Fatimid caliph-Imam al-Mahdi (d. 322/934) and his next three successors, ruling from Ifriqiya, encountered numerous difficulties while consolidating the pillars of their state. In addition to the continued animosity of the Abbasids, and the Umayyads of Spain, who as rival claimants to the caliphate entertained their own designs for North Africa, the early Fatimids had numerous military entanglements with the Byzantines. They also devoted much of their energy to subduing the rebellions of the Khariji Berbers, especially those belonging to the Zanata confederation, and the hostilities of the Sunni inhabitants of the cities of Ifriqiya led by their influential Maliki jurists. All this made it extremely difficult for the early Fatimids to secure control over any region of the Maghrib, beyond the heartland of Ifriqiya, for any extended period. It also made the propagation of the Ismaili da'wa rather impractical in the Maghrib. In fact, `Abd Allah al-Mahdi and his immediate successors did not actively engage in the extension of their da'wa in order to avoid hostile reactions of the majoritarian Khariji and Sunni inhabitants of North Africa. Nevertheless, the Ismailis were now for the first time permitted to practise their faith openly and without fearing persecution within Fatimid dominions, while outside the boundaries of their state they were obliged, as before, to observe taqiyya or precautionary dissimulation of their true beliefs.

Continuation of the da'wa and Codification of Ismaili Law

In line with their universal claims the Fatimid caliph-Imams had, however, not abandoned their da'wa aspirations on assuming power. Claiming to possess sole legitimate religious authority, the Fatimids aimed to extend their authority and rule over the entire Muslim umma and even the regions of the world inhabited by non-Muslims. As a result, they retained the network of da'is operating on their behalf both within and outside Fatimid dominions, although initially they effectively refrained from da'wa activities within the Fatimid state. It took the Fatimids several decades to formally establish their rule in North Africa. Only the fourth Fatimid caliph-Imam, al-Mu`izz (341-365/953-975), was able to pursue successfully policies of war and diplomacy, also concerning himself specifically with the affairs of the Ismaili da'wa. His overall aim was to extend the universal authority of the Fatimids at the expense of their major rivals, namely, the Umayyads of Spain, the Byzantines and above all, the Abbasids. The process of codifying Ismaili law, too, attained its climax under al-Mu`izz mainly through the efforts of al-Qadi al-Nu'man (d. 363/974), the foremost Fatimid jurist. Al-Mu'izz officially commissioned al-Nu'man, who headed the Fatimid judiciary from 337/948 in the reign of the third Fatimid caliph-Imam al-Mansur, to promulgate an Ismaili madhhab. His efforts culminated in the compilation of the Da‘a'im al-!slam (The Pillars of Islam), which was endorsed by al-Mu'izz as the official code of the Fatimid dawla. The Ismailis, too, now possessed a system of law and jurisprudence as well as an Ismaili paradigm of governance.

As developed by al-Nu'man. Ismaili law accorded special importance to the central Shi`i doctrine of the Imamate. In fact, the opening chapter in the Da`a'im al-Islam, which relates to walaya, explains the necessity of acknowledging the rightful Imam of the time, viz., the Fatimid caliph-Imam, also providing Islamic legitimation for the `Alid state ruled by the Fatimids belonging to the Prophet's family. In fact, the authority of the infallible Fatimid `Alid Imam and his teachings were listed as the third principal source of Ismaili law, after the Qur'an and the sunna of the Prophet which are accepted as the first two sources by all Muslims. In sum, it was al-Qadi al-Nu'man who elaborated in his legal compendia a doctrinal basis for the Fatimids' legitimacy as ruling caliph-Imams, also lending support to their universal claims.5

Religious Propaganda [sic] Within and Against the Fatimid dawla

Al-Mu'izz, as noted, was the first member of his dynasty to have concerned himself with the Ismaili da'wa outside Fatimid dominions. In addition to preparing the ideological ground for Fatimid rule, his da'wa strategy was based on a number of more specific religio-political considerations. The propaganda of the Qarmatis of Bahrayn, Iraq, Persia and elsewhere, who had continuously refused to recognise the Imamate of the Fatimids, generally undermined the Ismaili da'wa and the activities of the Fatimid da`is in the same regions. It was, indeed, mainly due to the doctrines and practices of the Qarmatis that the entire Ismaili movement was accused by the Sunni polemicists and heresiographers of ilhad or deviation in religion, as these hostile sources did not distinguish between the dissident Qarmatis and those Ismailis who acknowledged the Fatimid caliphs as their Imams. The anti-Ismaili literary campaign of the Sunni establishment, dating mainly to the foundation of Fatimid rule, was particularly intensified in the aftermath of the Qarmatis' sack of Mecca in 317/930. At any rate, al-Mu'izz must have also recognised the military advantages of winning the support of the formidable Qarmati armies, which would have significantly enhanced the chances of the Fatimids' victory over the Abbasids in the central Islamic lands. It was in line with these objectives that al-Mu`izz made certain doctrinal adjustments, rooted in the teachings of the early Ismailis and designed to prove appealing to the Qarmatis.6 Perhaps as a concession to the Qarmati camp, al-Mu'izz and the Fatimid da'wa also endorsed the Neoplatonised cosmology first propounded by the Qarmati da'i Muhammad al-Nasafi (d. 332/943) in his Kitab al-mahsul (Book of the Yeld) around 300/912. Henceforth, this new cosmology was generally advocated by the Fatimid da'wa in preference to the mythological Kuni-Qadar cosmology of the early Ismailis.7

The da'wa strategy of al-Mu'izz won some success in the dissident camp outside the confines of the Fatimid state. The da'i Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani, who had hitherto belonged to the Qarmati faction, switched his allegiance to the Fatimid da'wa. As a result, large numbers of the Qarmatis of Khurasan, Sistan (Arabicised, Sijistan), Makran and Central Asia, where al-Sijistani acted as chief da‘i in succession to al-Nasafi and his sons, also acknowledged the Fatimid Ismaili Imam. Al-Sijistani was executed as a heretic (mulhid) not long after 361/971 on the order of Khalaf b. Ahmad, the Saffavid amir of Sistan, but Ismailism survived in the eastern regions of the Iranian world. Fatimid Ismailism also succeeded in acquiring a permanent stronghold in Sind, in northern India, where Ismaili communities have survived to modern times. Around 347/958, through the efforts of a Fatimid da'i who converted a local Hindu ruler, an Ismaili principality was established in Sind, with its seat in Multan (in present-day Pakistan). Large numbers of Hindus converted to Ismailism in that region of the Indian subcontinent, where the khutba was read in the name of al-Mu`izz and the Fatimids. This Ismaili principality survived until 396/1005 when Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna invaded Multan and persecuted the Ismailis. Despite the hostilities of the Ghaznawids and their successors, however, Ismailism survived in Sind and later received the protection of the Sumras, who ruled independently from Thatta for almost three centuries starting in 443/1051.8 On the other hand, Qarmatism persisted in Daylam, Adharbayjan and other parts of Persia, as well as in Iraq and Central Asia for almost a century after al-Mu'izz. Above all, al-Mu'izz failed to win the support of the Qarmatis of Bahrayn, who effectively frustrated the Fatimids' strategy of eastern expansion into Syria and other central Islamic lands.

Meanwhile, al-Mu'izz had made detailed plans for the conquest of Egypt, a vital Fatimid goal which the first two members of the dynasty had failed to achieve. To that end, the Fatimid da'wa was intensified in Egypt, then beset by numerous economic and political difficulties under disintegrating Ikhshidid rule. Jawhar, the capable Fatimid commander who had pacified North Africa for al-Mu'izz, was selected to lead the Egyptian expedition. Having encountered only token resistance, Jawhar entered Fustat, the capital of Ikhshidid Egypt, in Sha'ban 358/July 969. Jawhar behaved leniently towards Egyptians, declaring a general amnesty. Subsequently, the Fatimids introduced the Ismaili madhhab only gradually in Egypt, where Shi'ism had never acquired a stronghold. Fatimid Egypt remained primarily Sunni, of the Shafi`i madhhab, with an important community of Christian Copts. The Fatimids never attempted forced conversion of their subjects and the minoritarian status of the Shi'a remained unchanged in Egypt despite two centuries of Ismaili Shi'i rule.

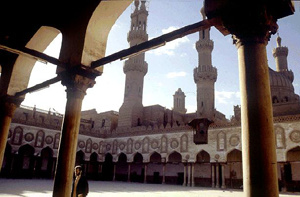

Jawhar camped his army to the north of Fustat and immediately proceeded to build a new royal city there, the future Fatimid capital al-Qahira (Cairo). Al-Mu'izz had personally supervised the plan of Cairo with its al-Azhar mosque and Fatimid palace complex. Jawhar ruled over Egypt for four years until the arrival of al-Mu'izz. In line with the eastern strategy of the Fatimids, in 359/969 Jawhar dispatched the main body of the Fatimid armies for the conquest of Palestine and Syria. In the following year, the Fatimids were defeated near Damascus by a coalition of the Qarmatis of Bahrayn, Buyids and other powers. Later in 361/971, the Qarmatis of Bahrayn advanced to the gates of Fustat before being driven back. Henceforth, there occurred numerous military encounters between the Fatimids and the Qarmatis of Bahrayn, postponing the establishment of Fatimid rule over Syria for several decades.9

In the meantime, al-Mu'izz had made meticulous preparations for the transference of the seat of the Fatimid state to Egypt. He appointed Buluggin b. Ziri, the amir of the loyal Sanhaja Berbers, as governor of Ifriqiya. Buluggin, like his father, had faithfully defended the Fatimids against the Zanata Berbers and other enemies in North Africa; and he was to found the Zirid dynasty of the Maghrib (361-543/972-1148). Accompanied by the entire Fatimid family, Ismaili notables, Kutama chieftains, as well as the Fatimid treasuries and the coffins of his predecessors, al-Mu`izz crossed the Nile and took possession of his new capital in Ramadan 362/June 973. In Egypt, al-Mu'izz was mainly preoccupied with the elaboration of Fatimid governance in addition to repelling further Qarmati incursions. Having transformed the Fatimid dawla from a regional power into an expanding and stable empire with a newly activated da'wa apparatus, al-Mu'izz died in 365/975.

Cairo served from early on as the central headquarters of the Fatimid Ismaili da'wa organisation that developed over time and reached its peak under the eighth Fatimid caliph-Imam al-Mustansir (427-187/1036-(094). The religio-political message of the da'wa continued to be disseminated both within and outside the Fatimid state through an expanding network of da'is. The term da'wa, it may be noted, referred to both the organisation of the Ismaili mission, with its elaborate hierarchical ranks or hudud, and the functioning of that organisation, including especially the missionary activities of the da'is who were the representatives of the da'wa in different regions.

Secrecy Surrounding da'wa Functioning

The organisation and functioning of the Ismaili da'wa are among the most secretly guarded aspects of Fatimid Ismailism. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Ismaili literature of the Fatimid period recovered in modern times has shed only limited light on this subject. Information is particularly meagre regarding the da'wa and the activities of the da'is in hostile regions outside the Fatimid dawla, such as Iraq, Persia. Central Asia and India, where the da'is, fearful of persecution, were continuously obliged to observe taqiyya and secrecy in their operations. All this once again explains why Ismaili literature is generally so poor in historiographical details on the activities of the da'is - information that in Fatimid times may have been available only to the central headquarters of the Ismaili da'wa, headed by the person of the Imam. However, modern scholarship in Ismaili studies, drawing on a variety of Ismaili and non-Ismaili sources, including histories of Egypt, has now finally succeeded to piece together a relatively reliable sketch of the Fatimid Ismaili da'wa, with some of its major practices and institutions.

The Fatimids, as noted, aspired to be recognised as rightful Imams by the entire Muslim umma: they also aimed to extend their actual rule over all Muslim lands and beyond. These were, indeed, the central objectives of their da'wa, which continued to be designated as al-da'wa al-hadiya, the rightly guiding summons to mankind to follow the Fatimid Ismaili Imam. The word da'i, literally meaning "summoner," was used by several Muslim groups and movements, including the early Shi'i ghulat, the Abbasids, the Mu'tazila, and the Zaydiyya, in reference to their religio-political missionaries. But the term acquired its widest application in connection with the Isma`iliyya, while the early Ismailis and Qarmatis in Persia and elsewhere sometimes used other designations such as janah (plural, ajniha) instead of da'i. It should also be noted that at least from Fatimid times several categories of da'is existed in any region. Be that as it may, the term da'i (plural, du'at) was applied generically to any authorised representative of the Fatimid da'wa, a missionary responsible for propagating Ismailism through winning new converts, and followers for the Ismaili Imam of the time. As the provision of instruction in Ismaili doctrine for the initiates was from early on an important responsibility of the da'wa, the da'i was also entrusted with the religious education of the new converts or mustajibs. Furthermore, the Ismaili da'i served as the unofficial agent of the Fatimid dawla, and promoted secretly the Fatimid cause wherever he operated. The earliest record of this aspect of the da'is activity is best exemplified in the achievements of the da'i Abu `Abd Allah al-Shi`i (d. 298/911) in North Africa. Within Fatimid dominions, the Ismaili da'wa was protected by the Fatimid dawla and doubtless some collaborative relationship must have existed between them as both were headed by the person of the caliph-Imam.10

Despite his all-important role, however, very little seems to have been written on the da'i by the Ismaili authors of Fatimid times. The prolific al-Qadi al-Nu'man, head of the da'wa for some time, devoted only a few pages to the virtues of an ideal da'i.11 He merely emphasises that the da'wa was above all a teaching activity and that the dai's were teachers who promoted their message also through their own exemplary knowledge and behaviour. A more detailed discussion of the attributes of an ideal da'i is contained in the only known Ismaili work on the subject written by the da'i - author Ahmad b. Ibrahim al-Nisaburi, al-Nu'man's younger contemporary.12 According to al-Nisaburi, a da'i could be appointed only by the Imam's permission (idhn). The dai's, especially those operating in remote lands outside Fatimid dominions, seem to have enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, and they evidently received only their general directives from the central da'wa headquarters. In these generally hostile regions, the da'is operated very secretly, finding it rather difficult to establish frequent contacts with the da'wa headquarters in Cairo.

Under these circumstances, only Ismailis of high educational qualifications combined with proper moral and intellectual attributes could become da'is leading Ismaili communities in particular localities. The da'is were expected to have sufficient knowledge of both the zahir and the batin dimensions of religion, or the apparent meanings of the Qur'an and the sharia and their Ismaili interpretation (ta'wil). In non-Fatimid lands, the da'i also acted as a judge in communal disputes and his decisions were binding for the members of the local Ismaili community. Thus, the da'i was often trained in legal sciences as well. The da'i was expected to be adequately familiar with the teachings of non-Muslim religions, in addition to knowing the languages and customs of the region in which he functioned. All these qualifications were required for the orderly performance of the da'i's duties. As a result, a great number of da'is were highly learned and cultured scholars and made important contributions to Islamic thought. They also produced the bulk of the Ismaili literature of the Fatimid period in Arabic, dealing with a diversity of exoteric and esoteric subjects ranging from jurisprudence and theology to philosophy and esoteric exegesis.13 Nasir Khusraw was the only major Fatimid da'i to have written his books in Persian.

Like other aspects of the da'wa, few details are available on the actual methods used by the Fatimid da'is for winning and educating new converts. Always avoiding mass proselytisation, the da'i had to be personally acquainted with the prospective initiates, who were selected with special regard to their intellectual abilities and talents. Many Sunni sources, influenced by anti-Ismaili polemical writings, mention a seven-stage process of initiation (balagh) into Ismailism, and even provide different names for each stage in a process that allegedly led the novice to the ultimate stage of irreligiosity and unbelief.14 There is no evidence for any fixed graded system in the extant Ismaili literature, although a certain degree of gradualism in the initiation and education of converts must have been unavoidable. Indeed, al-Nisaburi relates that the da'i was expected to instruct the mustajib in a gradual fashion, not divulging too much at any given time: the act of initiation itself was perceived by the Ismailis as the spiritual rebirth of the adept.

It was the duty of the da'i to administer to the initiate an oath of allegiance (ahd or mithaq) to the Ismaili Imam of the time. As part of this oath, the initiate also pledged to maintain secrecy in Ismaili doctrines taught to him by the da'i. Only after this oath the da'i began instructing the mustajib, usually in regular "teaching sessions" held at his house for a number of such adepts. The funds required by the da'i for the performance of his various duties were raised locally from the members of his community. The da'i kept a portion of the funds collected on behalf of the Imam, including the zakat, the khums and certain Ismaili-specific dues like the najwa, to finance his local operations and sent the remainder to the Imam through reliable couriers. The latter, especially those going to Cairo from remote da'wa regions, also brought back Ismaili books for the da'is. The Fatimid da'is were, thus, kept well informed on the intellectual developments within Ismailism, especially those endorsed by the da'wa headquarters.

Majalis and the Proliferation of Ismaili Ideology

The scholarly qualifications required of the da'is and the Fatimids' high esteem for learning resulted in a number of distinctive traditions and institutions under the Fatimids. The da'wa was, as noted, concerned with the religious education of converts, who had to be duly instructed in Ismaili esoteric doctrine or hikma. For that purpose, a variety of "teaching sessions", generally designated as majalis (singular, majlis), were organised. These sessions, addressed to different audiences, were formalised by the time of the Fatimid caliph-Imam al-Hakim (386-411/996-1021).15 The lectures on Ismaili doctrine, the majalis al-hikma, as noted, were initiated by the da'i Abu'Abd Allah al-Shi'i, and then systematised by al-Qadi al-Nu'man. In the Fatimid state, from early on, the private majalis al-hikma, organised for the exclusive benefit of the Ismaili initiates, were held separately for men and women. These lectures, delivered by the chief da'i (da'i al-du'at) who was often also the chief qadi (qadi al-qudat) of the Fatimid state, required the prior approval of the Fatimid caliph-Imam. There were also public lectures on Ismaili law. The legal doctrines of the Ismaili madhhab, adopted as the official system of religious law in the Fatimid state, were applied by the Fatimid judiciary, headed by the chief qadi. But the Ismaili legal code, governing the juridical basis of the daily life of the Muslim subjects of the Fatimid state, was new and its precepts had to be explained to Ismaili as well as non-Ismaili Muslims. As a result, public sessions on the sharia as interpreted by Ismaili jurisprudence, were held by al-Qadi al-Nu'man and his successors as chief qadis, after the Friday midday prayers, in the Fatimid capital. In Cairo, the public sessions on Ismaili law were held at al-Azhar and other great mosques there. On these occasions, excerpts from al-Nu'man's Da‘a'im al-Islam and other legal works were read to large audiences.

On the other hand, the private majalis al-hikma continued to be held in the Fatimid palace in Cairo for the Ismaili initiates who had already taken the oath of allegiance and secrecy. Many of these majalis, normally prepared by or for the chief da'i, were in time collected in writing. This distinctive Fatimid tradition of learning found its culmination in the Majalis of al-Mu'ayyad fi'l-Din al-Shirazi (d. 470/1078), chief da'i for almost twenty years under al-Mustansir. Fatimid da`is working outside Fatimid dominions seem to have held similar "teaching sessions" for the education of the Ismaili initiates. In non-Fatimid territories, the Ismailis observed the law of the land wherever they lived, while taking their personal disputes to local Ismaili da`is. The Fatimids paid particular attention to the training of their da`is, including those operating outside the confines of the Fatimid state. Among the Fatimid institutions of learning mention should be made of the dar al-'Ilm (House of Knowledge), founded in 395/1005 by al-Hakim in Cairo. A wide variety of religious and non-religious sciences were taught at this institution which was also equipped with a major library. Many Fatimid da`is received at least part of their education at the dar al-'Ilm.16 By later Fatimid times, the dar al-'Ilm more closely served the needs of the da'wa.

The Fatimid da`wa was organised hierarchically under the overall guidance of the Ismaili Imam, who authorised its general policies. It should be noted that the da'wa hierarchy or hudud mentioned in various Fatimid texts seems to have had reference to a utopian situation, when the Ismaili Imam would rule the entire world. Consequently, the da`wa ranks mentioned in these sources were not actually filled at all times: some of them were probably never filled at all. The chief da`i (da'i al-du'at) acted as the administrative head of the da`wa organisation He appointed the provincial da`is of the Fatimid state, who were stationed in the main cities of the Fatimid provinces, including Damascus, Tyre, Acre, Ascalon, and Ramla, as well as in some rural areas. These da`is represented the da`wa and the chief da`i, operating alongside the provincial qadis who represented the Fatimid qadi al-qudat. The chief da`i also played a part in selecting the da`is of non-Fatimid territories. Not much else is known about the functions of the chief da`i, who was closely supervised by the Imam. As noted, he was also responsible for organising the majalis al-hikma: and in Fatimid ceremonial, he ranked second after the chief qadi, if both positions were not held by the same person.17 The title of da'i al-du`at itself, used in non-Ismaili sources, rarely appears in the Ismaili texts of the Fatimid period which, instead, usually use the term bab (or bab al-abwab), implying gateway to the Imam's "wisdom", in reference to the administrative head of the da'wa organisation The da'i Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani makes particular allusions to the position of bab and his closeness to the Imam.18

Further Evolution of the da'wa Organisation

The organisation of the Fatimid da'wa, with its hierarchy of ranks, developed over time and reached its full elaboration under the caliph-Imam al-Mustansir.19 There are different references to the da'wa ranks (hudud) after the Imam and his bab. According to the idealised scheme, the world, specifically the regions outside Fatimid dominions, was divided into twelve jaziras or "islands" for da'wa purposes; each jazira representing a separate da'wa region. Delineated on the basis of a combination of geographic and ethnographic considerations, the "islands", collectively designated as the "islands of the earth" (jaza'ir al-ard), included Rum (Byzantine), daylam, standing for Persia, Sind, Hind (India), Sin (China), and the regions inhabited by Arabs, Nubians, Khazars, Slavs (Saqaliba), Berbers, Africans (Zanj), and Abyssinians (Habash).20 Other classifications of the "islands", too, seem to have been observed in practice. For instance, Nasir Khusraw refers to Khurasan as a jazira21 under his own jurisdiction; and this claim is corroborated by the well-informed Ibn Hawqal, who further adds that Baluchistan, in eastern Persia, belonged to that jazira. In this sense, Khurasan seems to have included neighbouring regions in today's Afghanistan and Central Asia. Among other regions functioning as jaziras of the Fatimid da'wa, mention may be made of Yaman as well as Iraq and western Persia, for a time headed by the da'i al-Kirmani.

Each jazira was placed under the overall charge of a high ranking da'i known specifically as hujja (proof, guarantor), also called naqib, lahiq or yad (hand) in early Fatimid times. The hujja was the highest representative of the da'wa in any "island", and he was assisted by a number of subordinate da`is of different ranks operating in the localities under his jurisdiction. These included da'i al-balagh, al-da`i al-mutlaq, and al da'i al-mahdud (or al-mahsur). There may have been as many as thirty such da`is in some jaziras.22 - The particular responsibilities of different da`is are not clarified in the meagre sources. It seems, however, that da'i al-balagh acted as liaison between the central da'wa headquarters in the Fatimid capital and the hujja's headquarters in his jazira, and al da'i al-mutlaq evidently became the chief functionary of the da'wa, operating with absolute authority in the absence of the hujja and his da'i al-balagh. The regional da'is, in turn, had their assistants, entitled al-ma'dhun, the licentiate. The sources mention at least two categories of this rank, namely, al-ma'dhun al-mutlaq, and al-ma'dhun al-mahdud (or al-mahsur), eventually called al-mukasir. The ma'dhun al-mutlaq often became a da`i himself; he was authorised as the chief licentiate to administer the oath of initiation and explain the rules and policies of the da'wa to the initiates, while the mukasir (literally, breaker) was mainly responsible for attracting prospective converts and breaking their attachments to other religions. The ordinary Ismaili initiates, the mustajibs or respondents who referred to themselves as the awliya' Allah or "friends of God", did not occupy a rank (hadd) at the bottom of the da'wa hierarchy. Belonging to the ahl al-da'wa (people of the mission), they represented the elite, the khawass, as compared to the common Muslims, designated as the ammat al-Muslimin or the 'awamm. The ranks of the Fatimid da'wa, numbering to seven from bab (or da'i al-du'at) to mukasir, together with their idealised functions and their corresponding celestial hierarchy, are elaborated by the da'i al-Kirmani.23

da'wa Within and Without the dawla

The Fatimid da'wa was propagated openly throughout the Fatimid state enjoying the protection of the government apparatus. But the success of the da`wa within Fatimid dominions was both limited and transitory, with the major exception of Syria where different Shi'i traditions had deep roots. During the North African phase of the Fatimid caliphate, Ismailism retained its minoritarian status in Ifriqiya and other Fatimid territories in the Maghrib where the spread of the da'wa was effectively checked by Maliki Sunnism and Kharijism. By 440/1048 Ismailism had virtually disappeared from the former Fatimid dominions in North Africa, where the Ismailis were severely persecuted after the departure of the Fatimids. In Fatimid Egypt, too, the Ismailis always remained a minority community. It was outside the Fatimid state, in the jaziras, that the Fatimid Ismaili da`wa achieved its greatest and most lasting success. Many of these "islands" in the Islamic world, scattered from Yaman to Transoxania, were well acquainted with a diversity of Shi`i traditions, including Ismailism, and large numbers in these regions responded to the summons of the Ismaili da'is. By the time of the Fatimid caliph-Imam al-Mustansir, significant Ismaili communities representing a united movement had appeared in many of the jaziras. By then, the dissident Qarmatis had either disintegrated or joined the dynamic Fatimid da`wa.

Al-Kirmani's Success and Abbasid Reactions

In Iraq and Persia, the Fatimid da`is had systematically intensified their activities from the time of the sixth Fatimid caliph-Imam al-Hakim. Aiming to undermine the Abbasids, they concentrated their efforts on a number of influential tribal amirs in Iraq, at the very centre of `Abbasid power. Foremost among the da`is of al-Hakim's reign was Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani (d. after 411 /1020), perhaps the most learned Ismaili scholar of the entire Fatimid period. Designated as the hujjat al`Iraqayn, as he spent a good part of his life as a chief da'i in both the Arab Iraq and the west-central parts of Persia, al-Kirmani succeeded in converting several local chieftains in Iraq, including the `Uqaylid amir of Kufa and several other towns who acknowledged Fatimid suzerainty. It was in reaction to the success of the da'wa in Iraq that the 'Abbasid caliph al-Qadir (381-422/991-1031) launched a series of military campaigns against the refractories as well as an anti-Fatimid literary campaign, culminating in the Baghdad manifesto of 402/1011 denouncing the Fatimids and refuting their `Alid genealogy.24 This manifesto was read from the pulpits throughout the 'Abbasid caliphate. It was also the learned da'i al-Kirmani who was invited to Cairo to refute, on behalf of the da`wa headquarters, the extremist doctrines then being expounded by the founders of the Druze movement.

da'wa Expansion in Iraq and Persia

The da'wa continued to be propounded successfully in Iraq, Persia, and other eastern lands even after the ardently Sunni Saljuqs had replaced the Shi'i Buyids as the real masters of the `Abbasid caliphate in 447/1055. Important Ismaili communities were now in existence in Firs, Kirman, Isfahan and many other parts of Persia. In Fars, the da'wa had achieved particular success through the efforts of the da'i al-Mu'ayyad fi' l-Din al-Shirazi, who had penetrated the ruling Buyid circles. After converting Abu Kalijar Marzuban (415-440/1024-1048), the Buyid amir of Fars and Khuzistan, and many of his courtiers, however, al-Mu'ayyad was advised to flee in order to escape `Abbasid persecution. Subsequently, he settled in Cairo, where he played an active part in the affairs of the Fatimid dawla as well as the Ismaili da'wa which he headed for twenty years from 450/1058 until shortly before his death in 470/1078. As revealed in his autobiography, al-Mu'ayyad played a crucial role as an intermediary between the Fatimid regime and the Turkish commander al-Basasiri who championed the Fatimid cause in Iraq against the Saljuqs and the Abbasids.25 In fact, al-Basasiri, with Fatimid help and al-Mu'ayyad's strategic guidance, seized several towns in Iraq and entered Baghdad itself at the end of 450/1058. In the 'Abbasid capital the khutba was now pronounced for al-Mustansir until al-Basasiri was defeated a year later. That Fatimid suzerainty was recognised in `Abbasid Iraq - albeit for only one year - attests to the success of the da'i al-Mu'ayyad and the da'wa activities there. Al-Mu'ayyad established close relations between the da'wa headquarters in Cairo and the local headquarters in several jaziras, especially those located in Yaman and the Iranian lands.

In Persia proper, the Ismaili da'wa had continued to spread in the midst of Saljuq dominions. By the 460s/1070s, the Persian Ismailis were under the overall leadership of a chief da'i, `Abd al-Malik b. `Attash, who established his secret headquarters in Isfahan, the main Saljuq capital. A religious scholar of renown and a capable organiser in his own right, `Abd al-Malik was also responsible for launching the career of Hasan Sabbah, his future successor and the founder of the independent Nizari Ismaili da'wa and state. Further east, in certain parts of Khurasan, Badakhshan and adjacent areas in Transoxania, the da'wa continued to be active with various degrees of success after the downfall of the Samanids in 395/1005.26 Despite incessant persecutions of the Ghaznawids and other Turkish dynasties ruling over those regions of the Iranian world, Nasir Khusraw and other da'is managed to win the allegiance of an increasing number to the Fatimid Ismaili Imam.

A learned theologian and philosopher, and one of the foremost poets of the Persian language, Nasir Khusraw spread the da`wa throughout Khurasan from around 444/1052, after returning from his well-documented voyage to Fatimid Egypt. As the hujja of Khurasan, he originally established his secret base of operations in his native Balkh (near today's Mazar-i Sharif in northern Afghanistan). A few years later, Sunni hostilities obliged him to take permanent refuge in the valley of Yumgan in Badakhshan. There, enjoying the protection of a local Ismaili amir, Nasir spent the rest of his life in the service of the da'wa. It is interesting to note that even from his exile in the midst of the remote Pamirs, Nasir maintained his contacts with the da'wa headquarters in Cairo, then still headed by the chief da'i al-Mu'ayyad. In fact, the lifelong friendship between al-Mu'ayyad and Nasir Khusraw dates to 439/1047 when both of these distinguished Persian Ismailis arrived in the Fatimid capital. On that occasion, Nasir stayed in Cairo for three years furthering his Ismaili education.27 It was evidently Nasir Khusraw who extended the da`wa in Badakhshan, now divided by the Oxus between Afghanistan and Tajikistan. At any rate, the modern-day Ismailis of Badakhshan, and their offshoot communities in Hunza and other northern areas of Pakistan, all regard Nasir Khusraw as the founder of their Ismaili communities. Nasir Khusraw died not long after 462/1070, and his mausoleum is still preserved near Faydabad, the capital of Afghan Badakhshan.

Nasir Khusraw was also the last major proponent of 'philosophical Ismailism', a distinctive intellectual tradition elaborated by the da'is of the Iranian lands during the Fatimid period. Influenced by the pseudo-Aristotelian texts circulating in the Muslim world, these da'is elaborated complex metaphysical systems harmonising Ismaili Shi'i theology with a diversity of philosophical traditions, notably Neoplatonism.28 The da'is of the Iranian lands, perhaps in reflection of their da'wa policy, wrote for the educated strata of society, aiming to appeal intellectually to the ruling elite. This may explain why these da'is, starting with al-Nasafi, expressed their theology in terms of the then most fashionable philosophical themes. This tradition has only recently been studied by modern scholars mainly on the basis of the numerous extant works of al-Sijistani, while Nasir Khusraw's contributions still remain largely unexplored. Be that as it may, these da`is of the Iranian lands elaborated the earliest tradition of philosophical theology in Shi'i Islam without actually compromising the essence of their message which revolved around the Shi'i doctrine of the Imamate.

The Ismaili da'wa achieved one of its major successes of the Fatimid times in Yaman, where Ismailism had survived in a subdued form after the initial efforts of the da'is Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman (d. 302/914) and Ibn-al-Fadl (d. 303/910. By the time of al-Mustansir, the leadership of the da'wa in Yaman had come to be vested in the da'i `Ali b. Muhammad al-Sulayhi, a chieftain of the influential banu Hamdan. In 429/1038 'Ali rose in the mountainous region of Haraz marking the foundation of the Sulayhid state. The Sulayhids recognised the suzerainty of the Fatimids and ruled over various parts of Yaman for more than a century. 'Ali al-Sulayhi headed the Ismaili da'wa as well as the Sulayhid state in Yaman, an arrangement that underwent several changes in subsequent times. By 455/1063, he had subjugated almost all of Yaman, enabling the da'wa to be propagated openly in his dominions.29 The Sulayhids established close relations with the Fatimid da'wa headquarters in Cairo, when al-Mu'ayyad was the chief da'i there. After 'Ali, who was murdered in a tribal vendetta in 459/1067, his son Ahmad al-Mukarrma succeeded as sultan to the leadership of the Sulayhid state, while the da'i Lamak b. Malik al-Hammadi (d. 491/1098) acted as the executive head of the Yamani da'wa.

From the latter part of Ahmad al-Mukarram's reign (459-477/1067-1084), when the Sulayhids lost much of northern Yaman to Zaydis, effective authority in the Sulayhid state was exercised by his consort, al-Malika al-Sayyida Hurra, a most remarkable queen and Ismaili leader.30 She played an increasingly important role in the affairs of the Yamani da'wa culminating in her appointment as the hujja of Yaman by al-Mustansir. This represented the first application of a high rank in the da'wa hierarchy to a woman. Al-Mustansir also charged her with the affairs of the da'wa in western India. The Sulayhids played a major part in the renewed efforts of the Fatimids to spread Ismailism on the Indian subcontinent, an objective related to Fatimid trade interests. At any rate, from around 460/1067, Yamani da`is were dispatched to Gujarat under the close supervision of the Sulayhids. These da'is founded a new Ismaili community in Gujarat which in time grew into the present Tayyibi Bohra community.

Fatimid Decline and Dissension

By the early decades of al-Mustansir's long reign (427-487/1036-1094), the Fatimid caliphate had already embarked on its political decline. In rapid succession, the Fatimids now lost almost all of their possessions outside Egypt proper, with the exception of a few coastal towns in the Levant. Al-Mustansir's death in 487/1094 and the ensuing dispute over his succession led to a major schism in the Ismaili da'wa as well, aggravating the deteriorating situation of the Fatimid regime. Al-Mustansir's eldest surviving son and heir designate, Nizar, was deprived of his succession rights by the scheming and ambitious al-Afdal, who a few months earlier had succeeded his own father Badr al-Jamali (d. 487/1094) as the all-powerful Fatimid vizier and "commander of the armies" (amir al-juyush). Al-Afdal installed Nizar's much younger half-brother Ahmad to the Fatimid caliphate with the title of al-Musta' li bi'llah, and he immediately obtained for him the allegiance of the da'wa leaders in Cairo. In protest, Nizar rose in revolt in Alexandria, but was defeated and executed soon afterwards in 488/1095. These events permanently split the Ismaili da'wa and community into two rival factions, designated as Musta'liyya and Nizariyya after al-Mustansir's sons who had claimed his heritage. The Imamate of al-Musta'li, who had actually succeeded his father on the Fatimid throne, was recognised by the da'wa organisation in Cairo, henceforth serving as central headquarters of the Musta'li Ismaili da'wa, and by the Ismailis of Egypt, Yaman and western India, who depended on the Fatimid establishment. In Syria, too, the bulk of the Ismailis seem to have initially joined the Musta'li camp. The situation was drastically different in the eastern Islamic lands where the Fatimids no longer exercised any political influence after the Basasiri episode.

The Nizaris Split from Fatimid Headquarters

By 487/1094, Hasan Sabbah, a most capable strategist and organiser, had emerged as chief da'i of the Ismailis of Persia and, probably, of all Saljuq territories. Earlier, Hasan had spent three years in Egypt, furthering his Ismaili education and closely observing the difficulties of the Fatimid state. On his return to Persia in 473/1081, Hasan operated as a Fatimid da'i in different Persian provinces while developing his own ideas for organising an open revolt against the Saljuqs. The revolt was launched in 483/1090 by Hasan's seizure of the mountain fortress of Alamut in northern Persia, which henceforth served as his headquarters. At the time of al-Mustansir's succession-dispute Hasan was already following an independent revolutionary policy; and he did not hesitate to uphold Nizar's rights and break off his relations with the Fatimid establishment and the da`wa headquarters in Cairo. This decision, fully supported by the entire Ismaili communities of Persia and Iraq, in fact marked the foundation of the independent Nizari Ismaili da'wa on behalf of the Nizari Imam who was then inaccessible. Hasan Sabbah also succeeded in creating a state, centred at Alamut, with vast territories and an intricate network of fortresses scattered in different parts of Persia as well as in Syria. Hasan Sabbah (d. 518/1124) and his next two successors at Alamut, Kiya Buzurg-Umid and his son Muhammad, ruled as da'is and hujjas representing the absent Nizari Imam. By 559/1164, the Nizari Imams themselves emerged openly at Alamut and took charge of the affairs of their da'wa and state.31 The Nizari state lasted for some 166 years until it too was uprooted by the Mongol hordes in 654/1256. However, the Nizari Ismaili da'wa and community survived the Mongol catastrophe. The Nizari Ismailis, who currently recognise the Aga Khan as their Imam, are today found in more than twenty-five countries of Asia, Africa, Europe and North America.

In the meantime, Musta'li Ismailism had witnessed an internal schism of its own with seminal consequences. On al-Musta'li's premature death in 495/1101, all Musta'li Ismailis recognised al-amir, his son and successor to the Fatimid caliphate, as their Imam. Due to the close relations then still existing between Sulayhid Yaman and Fatimid Egypt, Queen al-Sayyida, too, acknowledged al-amir's Imamate. The assassination of al-amir in 524/1130 confronted the Musta'li da'wa and communities with a major crisis. By then, the Fatimid caliphate was disintegrating rapidly, while the Sulayhid state was beset by its own mounting difficulties. It was under such circumstances that on al-amir's death, power was assumed as regent in the Fatimid state by his cousin `Abd al-Majid, while al-amir's infant son and designated successor al-Tayyib had disappeared under mysterious circumstances. Shortly afterwards in 526/1132, `Abd al-Majid successfully claimed the Fatimid caliphate as well as the Imamate of the Musta`li Ismailis with the title of al-Hafiz li-Din Allah. The irregular accession of al-Hafiz was endorsed, as in the case of al-Musta'li, by the da'wa headquarters in Cairo; and, therefore, it also received the support of the Musta'li communities of Egypt and Syria, who were dependent on the Fatimids. These Musta'li Ismailis, recognising al-Hafiz (d. 544/1149) and the later Fatimid caliphs as their Imams, became known as hafiziyya.

In Yaman, too, some Musta'lis, led by the Zuray'ids of `Adan who had won their independence from the Sulayhids, supported the Hafizi da'wa. On the other hand, the aged Sulayhid queen al-Sayyida who had already drifted apart from the Fatimid regime, upheld the rights of al-Tayyib and recognised him as al-amir's successor to the Imamate. Consequently, she severed her ties with Fatimid Cairo, much in the same way as her contemporary Hasan Sabbah had done a few decades earlier on al-Mustansir's death. Her decision was fully endorsed by the Musta'li community of Gujarat. The Sulayhid queen herself continued to take care of the Yamani da'wa supporting al-Tayyib's Imamate, later designated as Tayyibiyya. Until her death in 532/1138, al-Sayyida worked systematically for the consolidation of the Tayyibi da'wa. In fact, soon after 526/1132 she appointed al-Dhu'ayb b. Musa al-Wadi'i (d. 546/1151) as al-da'i al-mutlaq, or the da`i with absolute authority over the affairs of the Yamani da'wa. This marked the foundation of the independent Tayyibi Musta'li da`wa on behalf of al-Tayyib and his successors to the Tayyibi Imamate all of whom have remained inaccessible.32 The Tayyibi da`wa was, thus, made independent of the Fatimids as well as the Sulayhids: and as such, it survived the downfall of both dynasties. The Tayyibi da'wa was initially led for several centuries from Yaman by al-Dhu'ayb's successors as da`is. In subsequent times, the stronghold of Tayyibi Ismailism was transferred to the Indian subcontinent and the community subdivided into several groups: the two major (Da' udi-Sulaymani) groups still possess the authorities of their separate lines of da'i mutlaqs while awaiting the emergence of their Imam. The Tayyibi Ismailis have also preserved a good share of the Ismaili literature of the Fatimid period.

Ismaili Survival Amidst Fatimid Collapse

On 7 Muharram 567/10 September 1171, Saladin, ironically the last Fatimid vizier, formally ended Fatimid rule by instituting the khutba in Cairo in the name of the reigning `Abbasid caliph. At the time, al-`Adid, destined to be the seal of the Fatimid dynasty, lay dying in his palace. The Fatimid dawla collapsed uneventfully after 26 years amidst the complete apathy of the Egyptian populace. Saladin, the champion of Sunni "orthodoxy" and the future founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, then adopted swift measures to persecute the Ismailis of Egypt and suppress their da'wa and rituals, all representing the Hafizi form of Ismailism. Indeed, Ismailism soon disappeared completely and irrevocably from Egypt, where it had enjoyed the protection of the Fatimid dawla. In Yaman, too, the Hafizi da'wa did not survive the Fatimid caliphate on which it was dependent. On the other hand, by 567/1171 Nizari and Tayyibi da'was and communities had acquired permanent strongholds in Persia, Syria, Yaman and Gujarat. Later, all Central Asian Ismailis as well as an important Khoja community in India also acknowledged the Nizari da'wa. That Ismailism survived at all the downfall of the Fatimid dynasty was, thus, mainly due to the astonishing record of success achieved by the Ismaili da'wa of Fatimid times outside the confines of the Fatimid dawla.

1. See F. Daftary,

'The Earliest Ismailis", Arabica, 38 (1991), p. 214-345.

2. See, for example,

Abu Ja'far Muhammad b. Ya'qub al-Kulayni, al-Usul min al-kafi, ed. 'A.A.

al-Ghaffari (Tehran.1388/1963), vol. 1. p. 168-548.

3. On the schism

of 286/899 in Ismailism, and the subsequent hostile relations between the

Fatimids and the Qarmatis, see W. Madelung, "The Fatimids and the Qarmatis

of Bahrayn", in F. Daftary, ed., Mediaeval Ismaili History and Thought,(Cambridge,

1996), p. 21-73; F. Daftary, "A Major Schism in the Early Ismaili Movement",

Studia Islamica. 77 (1993), p. 123-139 and his "Carmatians", Encyclopaedia

Iranica, vol. 4, p. 823-832.

4. The propagation

of the Ismaili da'wa in North Africa, culminating in the establishment

of the Fatimid state, is treated in al-Qadi Abu Hanifa al-Nu'man b. Muhammad's

Iftitah al-da'wa, ed. W. al-Qadi (Beirut, 1970), p. 71-222; ed. F. Dachraoui

(Tunis, 1975), p. 47-257. See also F. Dachraoui. Le Califat Fatimide au

Maghreb, 296-365 H./909-975 JC. (Tunis, 1981), p. 57-122; F. Daftary, The

Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines (Cambridge, 1990), p. 134 ff., 144-173,

and H. Halm. The Empire of the Mahdi: The Rise of the Fatmids, tr. M. Bonner

(Leiden, 1996), p. 9-128.

5. See al-Qadi

Al-Nu'man, Da'a''im al-Islam, ed. A. A. A. Fyzee (Cairo, 1951-61), vol.

1, p. 1-98: partial English trans, The Book of Faith, tr. A. A. A. Fyzee

(Bombay, 1974), p. 4-111; A. Nanji, "An Ismaili Theory of Walayah in the

Da'a'im al-Islam of Qadi al-Nu'man ", in D. P. Little, ed., Essays on Islamic

Civilization Presented to Niyazi Berkes (Leiden, 1976), p. 260-273, and

I. K. Poonawala. " al-Qadi al-Nu'man and Ismaili Jurisprudence", in Daftary,

ed.. Mediaeval Ismaili History, p. 117-143.

6. S. M. Stern,

"Heterodox Ismailism at the Time of al-Mu'izz '", Bulletin of the School

of Oriental and African Studies,17 (1955), p. 10-33, reprinted in his Studies

in Early Ismailism (Jerusalem-Leiden, 1983), p. 257-288; W. Madelung. "Das

Imamat in der fruhen ismailitischen Lehre'", Der Islam, 37 (1961), p. 86-101,

and Daftary. The Ismailis, p. 176-180, where additional sources are cited.

7. On these developments,

see S. M. Stem, "The Earliest Cosmological Doctrines of Ismailism", in

his Studies, p. 3-29; H. Halm, "The Cosmology of the Pre-Fatimid Ismailiyya",

in Daftary, ed., Mediaeval Ismaili History, p. 75-83, and Paul E. Walker,

Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani: Intellectual Missionary (London, 1996), p. 26-103.

8. S. M. Stem,

"Ismaili Propaganda and Fatimid Rule in Sind", Islamic Culture, 23 (1949),

p. 298-307, reprinted in his Studies, p. 177-188; A. Hamdani. The Beginnings

of the Ismaili da'wa in Northern India (Cairo, 1956), p. 3-16, and Halm.

Empire of the Mahdi, p. 385-392.

9. The gradual

establishment and decline of Fatimid rule in Syria is treated at length

in Thierry Bianquis. Damas et la Syrie sous la domination fatimide, 359-468/969-1076

(Damascus, 1986-89), 2 vols.

10. See, for instance,

Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani, Ithbat al-nubuwwat, ed. `Arif Tamir (Beirut, 1966),

p. 91, 100, 128; W. Madelung and P. E. Walker, An Ismaili Heresiography:

The "bab al-Shaytan" from AbuTammdm's Kitab al-Shajara (Leiden, 1998),

text p. 7, 132, translation p. 26, 120, and A. Hamdani, "Evolution of the

Organisational Structure of the Fatimi da'wah", Arabian Studies, 3 (1976),

p. 85-114.

11. Al-Qadi al-Nu'man,

Kitab al-himma fiadab atba' al-a'imma, ed. M. Kamil Husayn (Cairo, 1948),

p. 136-140.

12. al-Nisaburi's

treatise, al-Risala al-mujaza al-kafiya fi adab al-du'at, has not been

recovered so far, but it has been preserved in later Ismaili sources. A

facsimile edition of the version preserved by Hasan b. Nuh Bharuchi (d.

939/1533), an Indian Ismaili scholar, is contained in Verena Klemm, Die

Mission des fatimidischen Agenten al-Mu'ayyad fi d-din in Shiraz (Frankfurt,

1989), p. 206-277. The same text provided the basis for W. Ivanow's "The

Organization of the Fatimid Propaganda", Journal of the Bombay Branch of

the Royal Asiatic Society, NS, 15 (1939), p. 18-35.

13. For a comprehensive

survey of this literature, see I. K. Poonawala. Biobibliography of Ismaili

Literature (Malibu, Calif.,1977), p. 35-132.

14. Shihab al-Din

Ahmad al-Nuwayri, Nihayat al-arab, vol. 25, ed. M. J. 'A. al-Hini et al.

(Cairo, 1984), p. 195-225: Ibn al-Dawadari, Kanz al-durar, vol. 6, ed.

S. al-Munajjid (Cairo, 1961), p. 97 ff.; `Abd al-Qahir b. Tahir al-Baghdadi.

al-Farq bayn al-firaq, ed. N. Badr (Cairo, 1328/1910), p. 282 ff., and

Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali, Fada'ih al-batiniyya, ed. 'Abd al-Rahman

Badawi (Cairo, 1964), p. 21-36.

15. Taqi al-Din

Ahmad al-Maqrizi, Kitab al-mawa'iz wa' l-i'tibar bi-dhikr al-khitat wa'

l-athar (Bulaq, 1270/1853-54), vol. 1, p. 390-391, vol. 2, p. 341-342;

H. Halm, "The Ismaili Oath of Allegiance (ahd) and the 'Sessions of Wisdom'

(majalis al-hikma) in Fatimid Times", in Daftary, ed., Mediaeval Ismaili

History, p. 91-115; his The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning (London,

1997), especially p. 23-29, 41-55, and P. E. Walker, "Fatimid Institutions

of Learning", Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 34 (1997).

p. 179-200.

16. Al-Maqrizi,

al-Khitat, vol. 1, p. 458-460, and Halm, The Fatimids, p. 71-77.

17. Ahmad b. 'Ali

al-Qalqashandi, Subh al-a'sha (Cairo, 1331-38/1913-20), vol. 3, p. 483,

vol. 8, p. 239-241, vol. 11, p. 61-66, and al-Maqrizi, al-Khitat, vol.

1, p. 391, 403.

18. Hamid al-Din

al-Kirmani. Rhaat al-`aql, ed. M. Kamil Husayn and M. Mustafa Hilmi (Cairo,

1953), p. 135, 138, 143. 152, 205-208, 212-214, 224, 260-262 and elsewhere.

19. See S. M.

Stern, "Cairo as the Centre of the Ismaili Movement", in Colloque international

sur l'histoire du Caire (Cairo, 1972), p. 437-450, reprinted in his Studies,

p. 234-256; P. E. Walker. "The Ismaili da'wa in the Reign of the Fatimid

Caliph

al-Hakim", Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 30 (1993),

p. 161-182; Daftary, The Ismailis. p. 224-232, and his "da'i", Encyclopaedia

Iranica, vol. 6, p. 590-593.

20. Al-Sijistani,

Ithbat, p. 172. al-Qadi al-Nu'man, Ta'wil al-da 'a'im, ed. M. H. al-A'zami

(Cairo, 1967-72), vol. 2, p. 74, and vol. 3, p. 48-49.

21. Nasir Khusraw,

Zad al-musafirin, ed. M. Badhl al-Rahman (Berlin, 1341/1923), p. 397, and

Ibn Hawqal, Kitab surat al-ard, ed. J. H. Kramers (2nd ed.. Leiden, 1938-39),

p. 310.

22. Nasir Khusraw,

Wajh-i din, ed. G. R. A'vani (Tehran, 1977), p. 178.

23. Al-Kirmani,

Rahat al'aql, p. 134-139, 224-225, also explained in H Corbin, Cyclical

Time and Ismaili Gnosis, tr. R. Manheim and J.W Morris (London, 1983),

p. 90-95. See also Nasir Khusraw, Shish Fasl, ed. And tr. W. Ivanow (Leiden,

1949), text p. 34-36, translation p. 74-77, his Wajh-i din,p. 255, and

R. Strothmann, ed., Gnosis Texte der Ismailten (Gottingen, 1943), p. 57,

82, 174-177

24. Al-Maqrizi,

Itti'az al-hunafa', ed. J. al-Shayyal and M. Hilmi M Ahmad (Cairo, 1967-73),

vol.1, p. 45-46

25. Al-Mu'ayyad

fi'l-Din al-Shirazi, Sirat al-Mu'ayyad fi'l-Din da'i al-du'at, ed. M. Kamil

Husayn (Cairo, 1949), especially p. 94-184, and Klemm, Die Mission, p.

2-63, 136-192.

26. For details,

see al-Maqrizi, ltti'az, vol. 2, p. 191-192; Ibn al-Athir, al-Kamil fi'

l-ta'rikh, ed. C. J. Tornberg (Leiden.1851?76), vol. 9, p. 211, 358. vol.

10, p. 122 ff., 165-166, and W. Barthold. Turkestan down to the Mongol

Invasion, ed. C. E. Bosworth (4th ed., London, 1977), p. 251. 304-305.

316-318.

27. Nasir Khusraw

describes the splendour and prosperity of the Fatimid capital most vividly

in his famous Safar-nama. ed. M. Dabir Siyaqi (Tehran, (356/1977). p. 74-99;

English trans. Naser-e Khosraw's Book of Travels (Safarnama), tr. W. M.

Thackston, Jr. (Albany. NY. 1986), p. 44-57.

28. For details

of the metaphysical systems of the Iranian da'is, as elaborated especially

in the works of al-Sijistani, see P. E. Walker, Early Philosophical Shi‘ism

(Cambridge, 1993), p. 67-142, and his The Wellsprings of Wisdom: A Study

of Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani's Kitab al-Yanabi` (Salt Lake City, 1994), especially

p. 37-111. The critical edition of al-Sijistani's Kitab al-yanabi`, together

with a summary French translation, may be found in H. Corbin, Trilogie

Ismaelienne (Paris-Tehran, 1961), text p. 1?97, translation p. 5-127. Al-Kirmani's

system, as propounded in his Rahat al-`aql, and its philosophical provenance,

are thoroughly studied in Daniel de Smet's La Quietude de 1'intellect:

Neoplatonisme et gnose Ismaelienne dans 1'oeuvre de Hamid ad-Din al-Kirmani

(Xc/XIc.) (Louvain, 1995). Of Nasir Khusraw's major theological-philosophical

texts, only two have been published so far in critical editions with translations

into European languages: see his Jami` al-hikmatayn, ed. H. Corbin and

M. Mu`in (Paris-Tehran, 1953); French trans. Le Livre reunissant les deux

sagesses, tr. I. de Gastines (Paris. 1990), and Gushayish va rahayish,

ed. S. Natisi (Tehran, 1961); ed. and tr. F. M. Hunzai as Knowledge and

Liberation (London, 1998).

29. The earliest

Ismaili accounts of the Sulayhids, and the contemporary da'wa in Yaman,

are contained in the da'i dris `Imad al-Din b. al-Hasan's `Uyun al-akhbar,

vol. 7, and his Nuzhat al-afkar, which are still in manuscript forms. The

best modern study here is Husayn F. al-Hamdani's al-Sulayhiyyun wa' l-haraka

al-Fatimiyya fi' l-Yaman (Cairo, 1955), especially p. 62-231.

30. See F. Daftary,

"Sayyida Hurra: The Ismaili Sulayhid Queen of Yemen", in Gavin R. G. Hambly,

ed.. Women in theMediaeval Islamic World (New York, 1998), p. 117-130,

where additional references are cited.

31. For the early

history of the Nizari da'wa and state, coinciding with the final eight

decades of the Fatimid dawla, see `Ata-Malik Juwayni, Ta'rikh-i jahan-gusha,

ed. M. Qazwini (Leiden-London, 1912-37), vol. 3, p. 186-239; English trans.

The History of the World-Conqueror, tr. J. A. Boyle (Manchester, 1958),

vol. 2, p. 666-697; Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Order of Assassins (The

Hague. 1955). p. 41-109, 145-159; B. Lewis, The Assassins (London, 1967),

p. 38-75; F. Daftary, "Hasan-i Sabbah and the Origins of the Nizari Ismaili

Movement", in Daftary, ed.. Mediaeval Ismaili History, p. 181?204, and

his The Ismailis, p. 324-391, 669-687, where full references to the sources

and studies are given.

32. On the early

histories of Musta`li Ismailism as well as the Hafizi and Tayyibi da'was,

see S. M. Stern, "The Succession to the Fatimid Imam al-amir, the Claims

of the Later Fatimids to the Imamate, and the Rise of Tayyibi Ismailism",

Oriens, 4 (1951), p. 193-255, reprinted in his History and Culture in the

Mediaeval Muslim World (London. 1984), article XI; A. Hamdani. "The Tayyibi

-Fatimid Community of the Yaman at the Time of the Ayyubid Conquest of

Southern Arabia", Arabian Studies, 7 (1985), p. 151-160, and Daftary, The

Ismailis, p. 256-286. 654-663.

![]() The True Meaning of Religion - Shihabudin Shah

The True Meaning of Religion - Shihabudin Shah

![]() Life

and Lectures of Al Muayyad fid-din al Shirazi

Life

and Lectures of Al Muayyad fid-din al Shirazi

![]() Nasir

Khusraw

Nasir

Khusraw

![]() More

Ismaili Heroes

More

Ismaili Heroes

History of the Imams

More History of the Imams By Abualy Aziz

| Present

Imam Shah Karim Aga Khan IV| 48th

Imam Mowlana Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan III | Hazrat

Ali | Prophet

Muhammad | Ismaili

Heroes | Poetry

| Audio Page | History

| Women's Page

| Legacy of

Islam | Current Events

|

Back to Ismaili Web

Back to Ismaili Web